Early Christianty and Reincarnation

The Jewish and Christian traditions were (and largely remain) inimical to reincarnation. All of the Christian theologians who spoke of reincarnation denounced it in no uncertain terms. The only break in the antireincarnationist view appears in the early writings of Origen, the third-century theologian who as a young man had converted to Christianity. Before his conversion he was an accomplished Platonist, and he attempted to integrate Platonic philosophy and Christian thinking in his earliest writings, which, if not affirming reincarnation, do speak of the preexistence of the soul and its possible transmigration. Origen later dropped his beliefs and in his biblical commentaries emerged as hostile to reincarnationist thought.

A major controversy involving Origen's early thought emerged in the sixth century surrounding a group of people who adopted Origen's early writings as part of their larger challenge to the Roman Empire. Thus it was that several councils reaffirmed the church's opinion on reincarnationist ideas and, in the style of the times, pronounced them anathema. In the early twentieth century, several proponents of reincarnation, primarily Theosophists working against the opposition of Christian leaders, countered with the story of a sixth-century plot. According to the idea, Christianity had taught reincarnation until the Roman empress Theodosia forced the church to edit the Bible and remove any reference to it. This theory shows a great ignorance of the history of the period and has no foundation in fact. In recent decades the primary presentation of this idea appeared in a book by Noel Langley, Edgar Cayce and Reincarnation, and has passed into New Age literature.

Gale Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology: Reincarnation

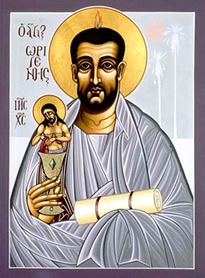

Origen

Born: c. 185 AD, Alexandria, Egypt

Died: c. 254 AD, Caesarea

Origen was a theologian, philosopher, and devoted Christian of the Alexandrian school. He famously castrated himself so he could tutor women without suspicion, and he risked his life countless times in encouraging martyrs. He himself was tortured under Decius as an old man and died a short time later. Origen's controversial views on the pre-existence of souls, the ultimate salvation of all beings and other topics eventually caused him to be labeled a heretic, yet his teachings were highly influential and today he is regarded as one of the most important early church fathers.

Works and Thought of Origen of Alexandria

Despite his brilliant mind, earnest spirituality, and important contributions to the development of Christian thought, Origen has received mixed reviews in Christian history. He had no lack of admirers in the first centuries after his death, most notably among them the church historian Eusebius and St. Jerome the scholar. But several regional synods of Catholic church (Alexandria in 399, Jerusalem, Cyprus) and perhaps one general council (Constantinople in 553) labeled him a heretic due to both his teachings and some wrongly attributed to him.

Perhaps Origen's greatest work is his great systematic theology: De principiis (On First Principles). Similar to the writings of Clement, it is an attempt to relate Christian faith to the philosophy of Alexandria - Neoplatonism. But his guiding principle was "nothing which is at variance with the tradition of the apostles and of the church is to be accepted as true."

Much of On First Principles is orthodox and mainstream Christian theology - he affirms one God, creator and ruler of universe, Jesus Christ begotten before creation who was divine in His incarnation, and the Holy Spirit's glory as no less than the Father and the Son. He explained that humans derive their existence from the Father, their rational nature from the Son, and their holiness from the Holy Spirit.

But Origen also enters into some great speculative flights in On First Principles, which would lead some church leaders to question his orthodoxy.

First, he proposed that there were two creations, which are narrated in the two accounts in Genesis. The first creation was of spirits without bodies. These spirits had free will, and some strayed from the purpose for which they were created - contemplation of the divine - and fell. This led to the second creation, the material creation. Those who fell farthest were made demons, while others became human. By extension, then, the reason we have human bodies and experience suffering is because of our sin in preexistence. Origen claims this notion is based in the Bible, but it is clearly influenced by Platonic tradition.

Another controversial topic in De principiis is universalism. Origen suggested that since God is love, everyone, even Satan, will be saved in the end (by endless opportunities for repentance, through learning and growth, even after death), and the entire creation will return to its original state where all was pure spirit.

On Reincarnation

In Greco-Roman thought, the concept of metempsychosis disappeared with the rise of Early Christianity, reincarnation being incompatible with the Christian core doctrine of salvation of the faithful after death. It has been suggested that some of the early Church Fathers, especially Origen still entertained a belief in the possibility of reincarnation, but evidence is tenuous, and the writings of Origen as they have come down to us speak explicitly against it.

The book Reincarnation in Christianity, by the theosophist Geddes MacGregor (1978) asserted that Origen believed in reincarnation. MacGregor is convinced that Origen believed in and taught about reincarnation but that his texts written about the subject have been destroyed. He admits that there is no extant proof for that position. The allegation was also repeated by Shirley MacLaine in her book Out On a Limb. Origen does discuss the concept of transmigration (metamorphosis) from Greek philosophy, but it is repeatedly stated that this concept is not a part of the Christian teaching or scripture in his Comment on the Gospel of Matthew (which survives only in a 6th-century Latin translation): "In this place [when Jesus said Elijah was come and referred to John the Baptist] it does not appear to me that by Elijah the soul is spoken of, lest I fall into the doctrine of transmigration, which is foreign to the Church of God, and not handed down by the apostles, nor anywhere set forth in the scriptures" (13:1:46–53, see Commentary on Matthew, Book XIII)

Debate

One of the great thinkers of early Christianity, Origen won by his speculative brilliance both admirers and antagonists within the church. Strongly influenced by Greek philosophy, Origen (at least in his earlier works) did teach the doctrine of pre-existence of the soul, that is, that humans were formerly angelic creatures whose good or bad deeds in the heavens resulted in a favorable or not-so favorable birth on earth. His writings on pre-existence, however, specifically denied transmigration after the initial incarnation of the soul. Even many Christian scholars are unsure as to whether or not Origen held to reincarnation, but it would seem that they have simply not read Origen thoroughly on this subject. In his commentary on Matthew, he directly considers this under the title "Relation of John the Baptist to Elijah — the Theory of Transmigration Considered":

In this place, it does not appear to me that by Elijah the soul is spoken of, lest I should fall into the dogma of transmigration, which is foreign to the Church of God and not handed down by the Apostles, nor anywhere set forth in the Scriptures. For observe, [Matthew] did not say, in the "soul" of Elijah, in which case the doctrine of transmigration might have some ground, but "in the spirit and power of Elijah."

In another place he says, "Let others who are strangers to the doctrine of the Church, assume that souls pass from the bodies of men into the bodies of dogs. We do not find this at all in the Divine Scriptures." His commentary on Matthew was written toward the end of his life (about 247), when he was over sixty years of age, and it most likely records his final opinions on the subject. His comments on John the Baptist and Elijah are followed by a lengthy refutation of the doctrine of transmigration.

For a scholarly approach to the subject see: Early Christianity and Reincarnation: Modern Misrepresentation of Quotes by Origen