The Fifth Council

The Fifth Ecumenical Council took place in Constantinople in 553 AD, and is also known as the Second Council of Constantinople. The Second General Council of Constantinople, of 165 bishops under Pope Vigilius and Emperor Justinian I, condemned the errors of Origen and certain writings (The Three Chapters) of Theodoret, of Theodore, Bishop of Mopsuestia and of Ibas, Bishop of Edessa; it further confirmed the first four general councils, especially that of Chalcedon whose authority was contested by some heretics.

Fifth Council

After Constantine and Nicaea, Origen's writings had continued to be

popular among those seeking clarification about the nature of Christ,

the destiny of the soul and the manner of the resurrection. Some of the

more educated monks had taken Origen's ideas and were using them in

mystical practices with the aim of becoming one with God.

After Constantine and Nicaea, Origen's writings had continued to be

popular among those seeking clarification about the nature of Christ,

the destiny of the soul and the manner of the resurrection. Some of the

more educated monks had taken Origen's ideas and were using them in

mystical practices with the aim of becoming one with God.

Toward the end of the fourth century, orthodox theologians again began

to attack Origen. Their chief areas of difficulty with Origen's thought

were his teachings on the nature of God and Christ, the resurrection and

the preexistence of the soul.

Their criticisms, which were often based on ignorance and an inadequate

understanding, found an audience in high places and led to the Church's

rejection of Origenism and reincarnation. The Church's need to appeal to

the uneducated masses prevailed over Origen's coolheaded logic.

The bishop of Cyprus, Epiphanius, claimed that Origen denied the

resurrection of the flesh. However, as scholar Jon Dechow has

demonstrated, Epiphanius neither understood nor dealt with Origen's

ideas. Nevertheless, he was able to convince the Church that Origen's

ideas were incompatible with the merging literalist theology. On the

basis of Ephiphanius' writings, Origenism would be finally condemned a

century and a half later.

Jerome believed that resurrection bodies would be flesh and blood,

complete with genitals - which, however, would not be used in the

hereafter. But Origenists believed the resurrection bodies would be

spiritual.

The Origenist controversy spread to monasteries in the Egyptian desert,

especially at Nitria, home to about five thousand monks. There were two

kinds of monks in Egypt - the simple and uneducated, who composed the

majority, and the Origenists, an educated minority.

The controversy solidified around the question of whether God had a body

that could be seen and touched. The simple monks believed that he did.

But the Origenists thought that God was invisible and transcendent. The

simple monks could not fathom Origen's mystical speculations on the

nature of God.

In 399 A.D., Bishop Theophilus wrote a letter defending the Origenist

position. At this, the simple monks flocked to Alexandria, rioting in

the streets and even threatening to kill Theophilus.

The bishop quickly reversed himself, telling the monks that he could now

see that God did indeed have a body: "In seeing you, I behold the face

of God." Theophilus' sudden switch was the catalyst for a series of

events that led to the condemnation of Origen and the burning of the

Nitrian monastery.

Under Theodosius, Christians, who had been persecuted for so many years,

now became the persecutors. God made in man's image proved to be an

intolerant one. The orthodox Christians practiced sanctions and violence

against all heretics (including Gnostics and Origenists),

pagans and Jews. In this climate, it became dangerous to profess the

ideas of innate divinity and the pursuit of union with God.

It may have been during the reign of Theodosius that the Gnostic Nag

Hammadi manuscripts were buried - perhaps by Origenist monks. For while

the Origenist monks were not openly Gnostic, they would have been

sympathetic to the Gnostic viewpoint and may have hidden the books after

they became too hot to handle.

The Origenist monks of the desert did not accept Bishop Theophilus'

condemnations. They continued to practice their beliefs in Palestine

into the sixth century until a series of events drove Origenism

underground for good.

Justinian (ruled 527 - 565 A.D.) was the most able emperor since

Constantine - and the most active in meddling with Christian theology.

Justinian issued edicts that he expected the Church to rubber-stamp,

appointed bishops and even imprisoned the pope.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire at the end of the fifth century,

Constantinople remained the capital of the Eastern, or Byzantine,

Empire. The story of how Origenism ultimately came to be rejected

involves the kind of labyrinthine power plays that the imperial court

became famous for.

Around 543 A.D., Justinian seems to have taken the side of the anti-Origenists

since he issued an edict condemning ten principles of Origenism,

including preexistence. It declared "anathema to Origen ... and to

whomsoever there is who thinks thus." In other words, Origen and anyone

who believes in these propositions would be eternally damned. A local

council at Constantinople ratified the edict, which all bishops were

required to sign.

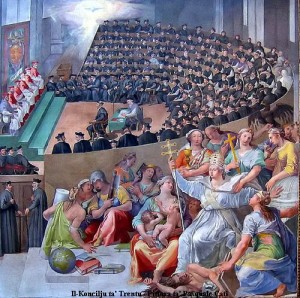

In 553 A.D., Justinian convoked the Fifth General Council of the Church

to discuss the controversy over the so-called "Three Chapters." These

were writings of three theologians whose views bordered on the

heretical. Justinian wanted the writings to be condemned and he expected

the council to oblige him.

He had been trying to coerce the pope into agreeing with him since 545

A.D. He had essentially arrested the pope in Rome and brought him to

Constantinople, where he held him for four years. When the pope escaped

and later refused to attend the council, Justinian went ahead and

convened it without him.

This council produced fourteen new anathemas against the authors of the

Three Chapters and other Christian theologians. The eleventh anathema

included Origen's name in a list of heretics.

The first anathema reads: "If anyone asserts the fabulous preexistence

of souls, and shall assert the monstrous restoration which follows from

it: let him be anathema." ("Restoration" means the return of the soul to

union with God. Origenists believed that this took place through a path

of reincarnation.) It would seem that the death blow had been struck

against Origenism and reincarnation in Christianity.

After the council, the Origenist monks were expelled from their

Palestinian monastery, some bishops were deposed and once again Origen's

writings were destroyed. The anti-Origenist monks had won. The emperor

had come down firmly on their side.

In theory, it would seem that the missing papal approval of the

anathemas leaves a doctrinal loophole for the belief in reincarnation

among all Christians today. But since the Church accepted the anathemas

in practice, the result of the council was to end belief in

reincarnation in orthodox Christianity.

In any case, the argument is moot. Sooner or later the Church probably

would have forbade the beliefs. When the Church codified its denial of

the divine origin of the soul (at Nicaea in 325 A.D.), it started a

chain reaction that led directly to the curse on Origen.

Church councils notwithstanding, mystics in the Church continued to

practice divinization. They followed Origen's ideas, still seeking union

with God.

But the Christian mystics were continually dogged by charges of heresy.

At the same time as the Church was rejecting reincarnation, it was

accepting original sin, a doctrine that made it even more difficult for

mystics to practice.